Stories

| Dachau | CMOH | Reunions | E-Mails | Memoirs |

THE INFANTRY RIFLEMEN The rifleman fights without promise of either

reward or relief.

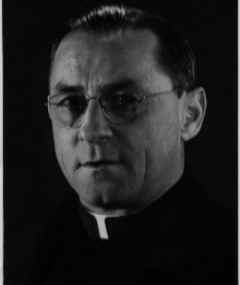

Born 10/7/1902 Died 9/25/1985 Father Barry's obituary appeared in the Province Review November 1985. REV. JOSEPH C. BARRY, CSC, of Holy Cross House, Notre Dame, died unexpectedly there on Wednesday, Sept. 25. He had joined the community as usual for supper the evening before and was apparently well. Death came as he was preparing to go to the chapel for the 7:a.m. community Mass at which he was a regular concelebrant. Fr. Barry born Oct. 7, 1902, in Syracuse, New York, graduated from Holy Rosary High School (source of several other Holy Cross vocations: Frs. Michael Foran, Theodore Hesburgh, Charles Young (EP) and the late Regis Riter), and entered Holy Cross Seminary in 1923. He went to St. Joseph's Novitiate a year later and made his first vows on August 15, 1925. After graduation from Notre Dame in 1929,he studied theology at Holy Cross College, Washington, D.C., and was ordained in Sacred Heart Church, Notre Dame, on June 24, 1933. Fr. Barry was first pastor of the new Christ the King

parish, South Bend, for his first year after ordination, then assisted at St.

Joseph's parish, South Bend, until 1941, a period interrupted only by a stint as

teacher and prefect at Notre Dame in 1935. As army chaplain with the Thunderbird

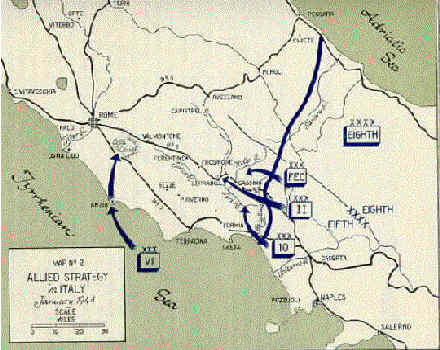

infantry division 1941-46 he survived some of the fiercest fighting of the war: in

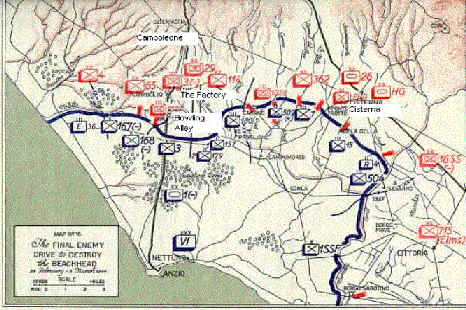

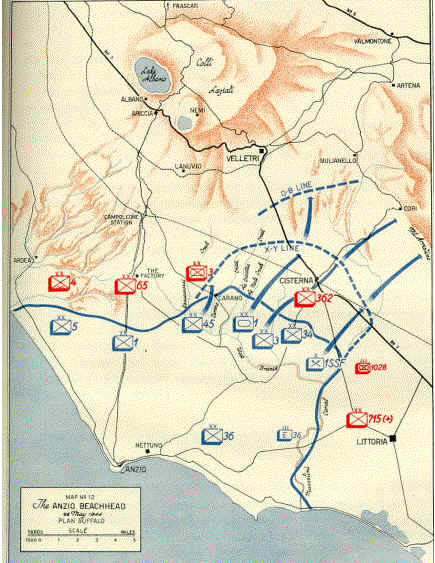

Africa, Sicily, Italy (Salerno and the Anzio Beachhead, the capture of Rome), and

finally the invasion of Southern France and Germany. After the war, he spent two

years as director of student affairs and prefect of discipline at Notre Dame, then

was associate vocation director during 1949-51. He returned to Notre Dame where he

was prefect of religion, pastor of Sacred Heart Church (1952-56) and assistant

prefect of religion (1956-61). After two years as chaplain at St. Joseph's Hospital,

South Bend, he was appointed chaplain at Archbishop Hoban High School, Akron, Ohio,

where he served for 19 years before ill health forced his retirement to Throughout his half century of priesthood, serving in a wide variety of apostolates, Fr. Barry was truly a sign of faith and hope and Christian joy for all those to whom he ministered. His three happy years at Holy Cross House were clear witness to these lifelong gifts. In his eulogy at the wake service in the Moreau Seminary chapel, Fr. William Craddick, assistant administrator and assistant superior of Holy Cross House, said: "At Hoban High School in Akron, happened what happened everywhere Father Joe went: he captivated young and old by his friendliness, cheerfulness and understanding. Many, and I mean many, Akron followers of Notre Dame football who came to home games would visit Father Joe at Holy Cross House and laugh with him. The Hoban High School affection for Father Barry was of no small degree. So beloved was he that when it came time to name the new gymnasium at the school, it was named after Father Joseph Barry." In his homily at the funeral Mass, Fr. Christopher O'Toole (SP) former superior general said: "Two years ago in this church, at this same hour, we celebrated the golden jubilee of Father Joe's ordination. Today we celebrate a victory, the victory of one who has persevered in his commitment to the end. We are here not just to pray for Father Joe, but also to pray with him, for he is a member of the Mystical Body of the Lord Jesus. We are here not to emphasize his physical absence, but to emphasize his spiritual presence-his union with us. He has been listening (to the Word of God) from the time he entered the seminary at Notre Dame. From that day to this the Word of God has been sounding in the depths of his soul. The Word of God pointing Father Joe to the religious life; to the novitiate; to perpetual profession and ordination to the priesthood. That Word has shaped his entire life…."

This article was written by Robert E. Donohue, Company E, 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th Division This incident happened in the Vosges Mountains during December 1944 while serving with Company E, 157th Infantry Regiment. Our company had made an attack during a full blown rain and ice storm and we ran into some major difficulties. During the fire fight I and another squad member name Strong got separated from the rest of the company. We unfortunately caught the attention of a concealed German machine gunner who began to systematically pursue the both of us in circles from tree to tree with a fusillade of bullets. We spotted a cavelike outcropping of rock on the side of a hill and dove for our lives under that rock. The German gunner had spotted us and persisted in hammering the rock and kept us captive unable to move out into the open. Since it was late afternoon we waited for full darkness to make a run for it, and we did. The machine gunner apparently heard us moving out, as he proceeded to blindly rake the hillside in hopes of picking off a hapless pair. The gunner failed to hit either of us, but in our haste and due to the pitch of darkness, I got tangled up in a mass of brushy undergrowth which caused me to trip and fall, resulting in the loss of my helmet. Later that night we made it back to our lines. I had just

managed to crawl up an embankment onto a muddy road when a three-quarter ton command

car skidded to a halt next to me and voice from within shouted: "Soldier, where

is your helmet?" Without waiting for a reply, a hand thrust a helmet through the

canvas side flaps and a voice said, The next morning when the company assembled to move out, I became the center of everyone's curiosity. Unknown to me, my new helmet had a bright silver cross on center front for all to see and wonder about. I learned later that the helmet donor was Father Barry the Regimental Chaplain. I kept the helmet for a long time, but Father Barry's silver cross lies somewhere in the woods of the Vosges mountains. (Father Barry retired to Notre University and is now deceased).

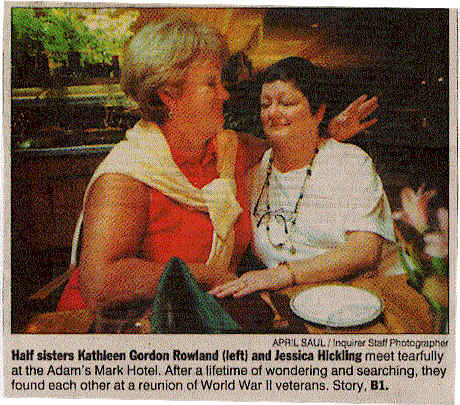

MY MOST REWARDING AND HAPPIEST REUNION My website http://www.45thInfantryDivision.com has been responsible for reuniting many people. This story is about a once in a lifetime occurrence. Jessica Hickling from Longmeadow, Mass. and Kathleen Gordon Rowland from Darien, Conn. saw an announcement on the front page of my website that the 157th Infantry Regiment was holding its reunion at the Adams Mark Hotel in Philadelphia, 6 to 9 September, 2000. Jessica and Kathleen did not know each other but decided to attend the reunion. Each was seeking information about their Dad, Robert A. Gordon, who served with Company "D", 157th Regiment, 45th Infantry Division and was killed 18 October 1944. Not only did they find information about their Dad but found each other. It was a very happy occasion and the climax of our reunion. I was exceptionally happy to have played a part in bringing Jessica and Kathleen together. My sincere wishes for continued happiness and joy to Jessica and Kathleen. The following story appeared in the Philadelphia Sunday Inquirer, 10 September 2000 written by Leonard N. Fleming. Al Panebianco

A lifetime of wondering, waiting ends in tears of joy for sisters Chance - and the Internet - bring WWII orphans together in Philadelphia. By Leonard N. Fleming Half sisters Jessica Hickling and Kathleen

Gordon Rowland never knew their father. And they had never laid eyes on each other.

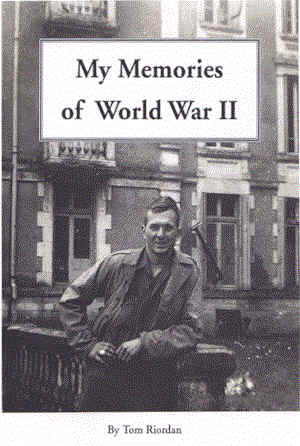

WORLD WAR II MEMORIES OF TOM RIORDAN Retired newspaperman Tom Riordan, a 60mm mortarman and communication sergeant for Company G, 157th Infantry 45th Division, tells us, “My wife Marilyn made me do it.” Riordan refers to a 72 page booklet about his World War II experiences, created as a Christmas gift for our six children and eleven grand kids. The project took three months. Actually I enjoyed the job. With a few tears here and there. Remembering Father Joseph Barry and buddies like Patty Williams, Orin Scott, Andy Korus, Wilmer Wood (who was killed at Bundenthal), George Courlas, Roland VanBuren, Bill Hundermark, Bill Lyford, plus other assorted characters. Riordan recounts his 35 month military career, from basic training at Fort McClellan, AL to Munich. Riordan told his offspring, “Please remember, Dad was not a war hero, just an ordinary soldier who always tried his best.” He dedicated the volume to seven of his 1940 classmates at Detroit Jesuit High School, all killed during WWII.

TOM

RIORDAN WORLD WAR II TIMELINE June 18, 1942: As a 21 year old sophomore at Michigan State

College, enlists in U.S. Army April 12, 1943: Basic training at Fort

McClellan, Alabama August 1943: Assigned to Camp Croft, South Carolina December l943: Joins 87th

Division in Camp McCain, Mississippi March 1944:

Transferred into European replacement pool April 1944:

Depart USA on troop ship with 4,000 replacements to fill ranks of Italian campaign

casualties. After speedy Atlantic crossing, arrive Oran, North Africa. May 1944:

With about 400 men taken by small British ship to Naples, Italy June l944:

In hills near Rome, assigned to Company G, 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th

Division as a 60mm mortarman. Given one-day pass to visit Rome. July 1944

In area near Naples, 45th rebuilt and trains for amphibious landing into Southern

France near St. Maxine. August 15, 1944: Invasion of southern France. Next four months: Combat with 45th battling through

Vosges Mountains along western edge of France into Alsace. December 17,1944: Bundenthal, Germany hospital and Midnight Mass

Christmas Eve. January 13, 1945: Reipertswiller, France, one of 13 survivors from

Company G. January 26, 1945: Hangwiller, Alsace to refit 157th,

promoted to company communications sergeant. March 14, 1945: Transferred to 45th public

relations to write releases for hometownpapers of men winning decorations. May 7, 1945: Germany

surrenders May 30, 1945: Transferred into

Army of Occupation, serving as sports editor of Ninth Division News. October 1945: Shipped to USA

on USS General Breckenridge. October 24, 1945: Discharge from Army at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. January

1946: Return

to Michigan State to complete college. AUGUST 15, 1944 – THE REAL THING Men of the 45th Division

boarded giant LSTs – Landing Ships Tank – in early August at Naples harbor. Navy

ships of various sizes escorted us, their big guns ready to pummel German defense

emplacements. This was it. The amphibious invasion of southern France. On the morning of the 15th we

were aroused at 2 o’clock for breakfast. We ate quietly. “Hope this goes like

the Anzio landing,” an old timer said. “No Germans to meet us.” Another

replies, “Sure as hell not like Sicily. That was a real SNAFU.” Father Joe Barry, the 45th’s

Catholic Chaplin, who served as a dorm moderator at Notre Dame before joining the army,

reminded us there would be a Mass in the hold of the ship at 4:00AM. By 3:30 it was

packed, GIs sitting on tanks, jeeps, trucks, boxes of ammunition and rations. Just before starting Mass, Father Barry

asked if someone could serve. I looked around. No one had volunteered. So I raised my

hand. “Father I can serve, but I don’t know all the Latin responses.” “That’s

OK soldier, I’ll answer the ones you can’t.” There I was, kneeling on the wide, wooden

ribs of the LST hold. Father beginning, “In the nomie Patris, et Fili, et Spiritus

Scanti. Amen.” I wondered, will this be my last Mass? Praise God. It wasn’t. For Company G, the actual landing was a

breeze. In our sector heavy dawn bombardments by naval guns had silenced German pill

boxes. Not a shot was fired by the Germans or us. Slogging through heavy sand, we saw

French civilians watching at the edge of the beach. They were cheering. For me, there was

one surprise. A plump, middle-aged French woman rushed towards us. Without warning, she

planted a wet kiss on my cheek. Our orders were to keep moving until we

ran into resistance. We force marched for two days, mainly through rain, until reaching a

little town called LeLuc – my baptism under fire. It lasted about 20 minutes. We set

up our mortars, but they weren’t needed. The Germans has quickly pulled back off. Our company commander was about to signal

us to move out when four French civilians joined him. They wore armbands with the letters

FFI. We were seeing our first Free French resistance fighters. “Anyone in the outfit

speak French?” the CO asked. George Courlas stepped forward. The Frenchmen excitedly

began to chatter and wave their arms. George listened carefully. “They say

there’s a German Mark IV tank hidden in the next village, sir. They want to knock it

out.” “OK,

tell ‘em to go ahead and do it.” And they did. As the weeks wore on we were in a variety

of battles. For some, our mortars played solid support roles. In others we dug into

defensive positions and waited. There were respites, even rest camp respites, hot showers

and fresh uniforms. But mostly we continued to move along the northeast border of France. My intention here is not to go into great

details about these actions, settling on two in Germany, which I remember best. The official history of the 157th

Infantry states: “The mission of the 45th was to break through the back

door into Germany by way of the Vosges Mountains.” That mission was accomplished. Company G contributed its share. NORTHWEST RECORD PEASANT GIVES FRESH MILK TO

DOUGHBOYS IN FRANCE

By PFC Tom Riordan November 3, 1944 (France, Oct 6) – The French people

are a sight to behold; their bright smiles and cheery greetings make a real hit with the

American soldiers. Bedecked in wooden shoes, the men in baggy pants and the women in long

plain dresses, the townsfolk are in front of their homes at all hours of the day and night

to greet the doughboys as they tramp through in pursuit of the Germans. Ever so often the

GIs would find a bottle of wine or basket of fruit offered to them. One of the nicest gifts I received while

our outfit was hoofing along on a very cool, rainy day was a bowl of rich warm milk just

taken from the cow. When the company halted for a break, our platoon stopped opposite a

tiny farmhouse. We had hardly sat down and loosened our equipment for the ten minute rest period, when the farm owner came

hustling out of his home with a big pail of milk. Following close at his heels were his wife and two children all clutching

little china bowls. They immediately began serving the

soldiers and everybody was smiling. As I sipped from the bowl offered me the chilly

feeling left my body and I felt good all over. “Merci, monsieur,” we told the

friendly peasant man of the soil, and proceeded to load him down with all our extra

cigarettes. American tobacco hasn’t been seen in France since the Nazi domination

four years ago, and the French smoker has had to puff on rationed German,

“tabac,” which has a large content of wood shavings in it. The smell of it burning is enough to make

even the veteran G.I. smoker take off for the nearest exit. It’s horrible, but taking a whiff of it helps you realize how much the

Frenchmen must appreciate our little gifts. This

unexpected act of love by a French farm family ranks as one of the sweetest events of my

nearly 18 months in Europe during WWII. Imagine a blustery and rain November day, a forced

march which seems to have no ending. That’s what the guys of Company G had going for

ourselves. Presto, warm milk to sip from bowls. Fresh from the cows. That was a treat. TWO TINY GERMAN TOWNS WITH

JAWBREAKER NAMES Let’s

start with Bundenthal during mid-December 1944. We’d been slogging through a deep

snowfall in a forest of giant trees. As guys in the ranks, we had no idea we were entering

a tiny corner of Germany. Or that the Siegfried Line was not many miles away. It was

late afternoon when we stopped. An officer huddled with the mortar squads. He said he had

a small force of GIs had been trapped in Bundenthal. Along with about 25 riflemen

we’d be strolling down the hillside and quietly rescue these GIs. Our

mission would start in about 45 minutes when it got dark. That left time for us to relax

from the day’s hike and enjoy a K-ration dinner. When

word to move came, we gathered our mortars, wondering what role they might play in the

rescue. As it turned out none. Moving out single file, we slipped and slid down an icy

path, which ran next to a large ditch . At the bottom of the hill the line of riflemen

turned left at a road and we followed. I

noticed a wrought iron fence running along next to us. Suddenly there was a burst of

German machine gun fire. We dove into a shallow ditch near the fence. Rifles began to pop.

Our guys were in a fire fight. The Germans had apparently waited until most of the column

had entered the town, then opened up. Now the rescue mission was itself part of the

beleaguered. We

crawled back along the fence and discovered an entrance into a cemetery. The lieutenant

decided we should hide among the tombstones. He said we’d head back up the hill at

dawn. That’s when we learned the ditch we’d seen in near darkness turned out to

be a giant tank trap. It was cut in a series of ledges to the top of the hill. He told us

to climb it, hopping up one ledge at a time. That worked fine until a German machine

gunner spotted our exit and began firing at us. Just

ahead of me Andy Korus of Texas yelled, “I’m hit in the leg.” I jumped to

his ledge. Both of us hugged the ground while

I tended his wound. There was another burst of fire, which just missed us. But tragically

Corporal Wilmer Wood of New Jersey. Bounding up to our ledge, was hit in the throat and

killed instantly. From that point there was nothing Andy and I could do but lay perfectly

still, pretending to be dead. At

dusk, stretcher bearers slid down the hill to remove Wilmer’s body. Another twosome

evacuated Korus. One of them told me, “The doctor says for you to come back with

us.” At the

aid station Andy was loaded into an ambulance. His war was over. (Fifty-five years later I

learned Korus was alive, albeit with a balky left knee. We exchanged letters. Andy said he

never knew the circumstances of being hit. So I filled him in.) The

field doctor pinned a “combat fatigue” tag on my jacket and said to join a group

of walking wounded. We soon were in an ambulance, bumping over rough roads, headed for a

small German hospital, taken over by U.S. Medical personnel. It was probably a dozen or so

miles from Bundenthal. You

may remember my Christmas 1944 story which ran in the Ocala Star-Banner. It recounted this

experience. Midnight Mass in the hospital chapel with about 75 GIs attending. The magic

moment when from the choir loft there was a burst of feminine voices, singing “Silent

Night” – in German. It turned out they were nuns who made up the hospital’s

regular nursing staff. My

story ended Christmas morning when Red Cross ladies passed out tiny gifts to patients. A

cake of soap, a razor, some shaving cream. Each was gaily wrapped in Yule paper. When a

gift-giver arrived at my bed she said softly, “I’m sorry, soldier, you arrived

after we made our head count. So there isn’t a present for you.” “That’s OK,” I smiled broadly, “I’ve already received the best gift of all – my life.” THREE BITTER DAYS AT REIPERTSWILLER About 50 years after the war ended I learned details of our battle near this town in France. It took place in late January, 1945. And I was there. What we didn’t know then, a rested,

well-supplied German SS mountain division, had swung down from Norway to the quiet

southern front, for one final all-out German assault. The combat-weary, undermanned 157th

Infantry was in the midst of being relieved by green troops. That spelled disaster. German 88 guns pounded American positions for three days. When the artillery lifted, Germans effectively infiltrated our strung-out forward positions, killing and capturing dozens of our men. The third day proved the most intense for

Company G mortar guys. Firing our guns almost continuously, we seemed to play tit for tat

with German mortarmen on the other side of the hill. “We’d let go a dozen

rounds. Before the third or fourth hit their lines, German incoming had us diving into

bunkers. First Sergeant Lou Wims led Company

G’s battered defensive force of maybe 40 riflemen atop the hill. He told us over our

direct-wire telephone hookup to pour out everything we had onto the attacking Germans. That led us to break the first commandment of firing a mortar: Only the gunner shall drop a round down the tube. But the hellish German counter battery that third day at Reipertswiller forced us into a forbidden technique. We would spread a GI blanket next to our bunker. Onto to it we placed about a dozen 60mm rounds.We tore off three of the four power bags (since our range was about 300 yards) and pulled each firing pin. Two guys would drag the blanket over the frozen ground to a mortar. Laying flat on each side of the gun, the pair took turns dropping rounds down the tube. When the blanket was empty, the pair scrambled for cover. On one such turn, a tail fin from my

buddy’s round, then exiting the tube, lightly sliced across a fingernail on the hand

I held a shell about to be dropped in. Yes, that scared the hell out of me. If my hand had

been a millimeter closer we could have been the only crew in the ETO (European Theater of

Operations) to self destruct firing our guns. Four years ago, Chan Rogers who later joined G Company called me about a reunion of the 157th in Myrtle Beach, SC. In the conversation Chan told me about a military historian was writing a book about the infamy of Reipertswiller. I contacted author Hugh Foster, a retired lieutenant colonel of the Vietnam era, to ask for data on those devastating days. Hugh sent me copies of his detailed research on the entire operation. From this I learned the gruesome facts. Most depressive were the statistics: the 157th Infantry suffered 158 killed, 426 captured and 600 wounded. Five companies, including G were completely gutted. Another author, Flint Whitlock, who wrote

a history of the 45th Division, entitled Rock of Anzio, reported, “The

battle of Reipertswiller was the most devastating single loss in the history of the 157th

Regiment.” When we remnants of Company G were pulled back, I counted 13 men.

WWII EXPERIENCES OF TECHNICAL SERGEANT RALPH W. FINK

Ralph Fink was sworn into military service at Allentown, PA on 3 March 1943. Left home on 10 March 1943 by train for New Cumberland, PA Induction Center. After several days there, entrained for Camp Wolters, TX for thirteen weeks of basic training. He then took a troop train to Camp Shenango, PA. This was a stop-over, waiting for overseas shipment. After about two weeks, shipped to Camp Shanks, NY and then boarded USS Alexander for shipment to Oran, Africa. After two weeks on the high seas and several replacement camps, he was assigned to Company “D”, 157th Regiment, 45th Infantry Division at Benevento, Italy, approximately 10 October 1943. Remained with Company “D” for the remainder of the war.

SANFORD KEITH BOWEN

Born 8/13/1918 - West Salem, OH. KIA 1/20/1945 - Reipertswiller, France Above is a picture of Sanford Keith Bowen with some of his buddies of the 1st Platoon, Company "I", 157th Regiment, 45th Infantry Division. This picture was taken December 16, 1944. He is in the front row, wearing glasses. Even at this late date, we are hoping that someone will recognize Keith and contact us. In the June 15, 1989 157th Infantry Association Newsletter, General Sparks related the following: "In early January of 1945, the German Army launched an attack towards the Alsatian Plains with the objective of breaking through to disrupt the Allied attack. This left the 45th Division, then already in Germany, in an exposed position, and the division was ordered to withdraw. The regiment withdrew to positions around Reipertswiller to counter the German penetration, known as the Bitche salient. Compounding the situation at the time, was the fact that the 45th Division had been in almost continuous combat for the preceeding 5 months. The fighting in the heavily forested Vosges Mountains and the subsequent penetration across the German border had been bitter and costly. Rain, snow, and mud made life miserable and supply difficult. Along with heavy battle casualties, sickness, and frozen feet resulted in severely depleted company strengths. There was probably not a rifle company in the division which could muster more than two-thirds of its full compliment of the men. Because of the Battle of the Bulge then nearing its conclusion, the Seventh United States Army, of which the 45th Division was a part, had been stripped of both replacements and units. The failure of their Ardennes offensive, known as the Battle of the Bulge, left the Germans desperate for a victory. In such desperation, a plan was conceived to drive Allied forces fromt he Vosges Mountains of Northern France. Fresh German troops were brought in, and the offensive against the thinly held Allied lines began. Standing squarely in the path of the German drive was the 45th Infantry Division and the 70th Infantry Division, newly arrived from the States, along with supporting troops. And such was the situation in which the exhausted troops of the 45th Division found themselves in early January of 1945, along with bone-chilling snowstorms. On the morning of January 14, 1945, the regiment, along with other elements of the division, launched a counterattack against the penetrating German forces. The ensuing battle lasted until the evening of January 20. While the German penetration was stopped, the regimental casualties were the heaviest of any single battle of the war. Companies C, G, I, K, L, and M were almost completely wiped out. Other units of the regiment also incurred heavy losses." Sanford (Sandy) Reed Bowen, son of Keith is currently writing, "The Biography of my father, Sanford Keith Bowen, a citizen soldier of WWII." Sandy and I have emailed each other for nearly two years and have met personally at our last two reunions. I am certain Keith would be very proud of his son. A great guy and a true gentleman.

DONUT DOLLIES CAPTURE A

"JERRY"

One morning Donut Dollies Monica (Woods) and Jo

(Betty Jones) took a jeep loaded with doughnuts for a run to a company just pulled

back into a 2nd position. Near to the company, the girls rode into a forest and

suddenly a "German Soldier" jumped out holding his hands up. Fortunately

they put the "Jerry" on the radiator and drove into the company area with

their capture. You can imagine what happened—that two Donut Dollies could capture a

"POW."

Before her demise, 1/20/96, Sally Stauffer donated all her Red Cross WWII memorabilia to the 45th Infantry Division Museum located in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. While visiting the museum, I was able snap a picture of Sally’s Red Cross uniform being displayed on a mannequin. In a frame standing beside the mannequin is this description: "This Red Cross uniform was worn by Ms. Sally Stauffer who as a "Donut Dolly" served the 45th Infantry Division during most of its 511 days of combat during WWII". Sally was part of our group when we visited Europe in 1989.

On part of the trip she wore her Red Cross uniform and like a true "Donut

Dolly" she distributed literature and other goodies in towns where our bus

stopped. A dedicated "Donut Dolly" to the very end. Sally was a

very charitable person and a gal I will never forget. By Al Panebianco

LTC Hugh F. Foster III (Ret.) taken 9/88 at

the The following articles were written by LTC Hugh F. Foster III (Ret.). Hugh is writing a book on the Reipertswiller encounter. FORWARD (Outline) There is a hierarchy in an army in peace and in war, and each layer has its special function. For some, the conditions don't change whether it be peace or war. Others live a more spartan existence by moving into tents. At the lower end of the hierarchy however, there is a most fundamental change in wartime: people are physically and psychologically maimed, and many die. Most soldiers in a wartime army will never hear a shot fired in anger. However, is a time-honored, and much used army expression as true today as it was when coined. Shit flows down hill. In war, nowhere is the expression more apt than in describing the infantry, for the greatest burden of the killing and the dying rests with those soldiers. At this level, shots in anger are heard -- and felt. Fear, love, grief, and sacrifice defy adequate definition. Yet, these are the adjectives that best describe an infantryman's life in combat. Fear is the common thread; it binds all infantrymen together. It is a constant companion, sometimes close and clawing, sometimes lurking just below the surface of consciousness. It is usually controlled by force of will but it possesses every infantry soldier at one time or another. For an infantryman every step, every movement, each bend in the road, each house could be his last. The infantryman of WWII worked day and night. For those who lived there were infrequent and very brief respites that came without notice -- a brief spell in "reserve", a slight wound. The nights passed with four one-hour spells of restless sleep at best, many times with no sleep at all. Every day someone around him, someone looked upon as a family member, was killed, wounded or just disappeared. He performed his duty outdoors, among the elements, in the rain and in the snow regardless of the heat or cold. He rarely tasted hot food; for days or weeks he ate only cold food from cans. A change of clothes, an opportunity to wash his body were even more rare than hot food. Maybe, every month or so he got clean clothes and a shower. He lived like this, suffered this misery until he was killed, badly wounded, captured, or the war ended; for most infantrymen, these were the only ways out of the line. It was an utterly miserable experience, seemingly without end. As bleak as this sounds, the description is not adequate. The reality is that an infantryman's life in combat is much more terrible than words can convey. Just as the experience of childbirth cannot be adequately explained to one who has not been through it; the reality of infantry combat defies adequate description. Most battles, including the fight north of Reipertswiller, are strategically not decisive, and are ignored by historians, who concentrate on the big picture. This approach is a grave injustice to the vast majority of infantry soldiers, those who suffer, serve, and die for obscure objectives, for a nameless hill or a patch of trees. What follows is more than the story of the 157th Infantry at Reipertswiller; it is a story of ordinary riflemen in WWII, for there are many thousands who shared similar experiences and who have not been recognized by history -- or by their families or neighbors. What follows is not a story of a critical battle; the fate of a campaign did not hinge on a couple of hilltops north of Reipertswiller. Strategic eyes had never seen the name. But men suffered and men died there, for a piece of ground that meant nothing in the big picture. Few operations are strategically important; it is the whole that matters in war, the sum of thousands of small battles. It is the infantryman's lot to suffer and to die so that cumulative efforts, never perceived at his level, succeed. This is a story of infantry men, ordinary men who served their country in extraordinary ways. This is a story of heroes.

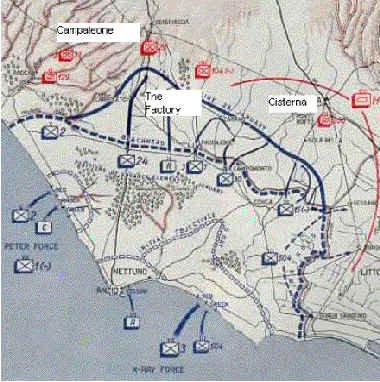

By the end of December, 1944, the 157th Infantry Regiment had seen more than 365 days of combat. The Regiment had deployed to North Africa with its parent division, the 45th Infantry Division, where it trained for and then conducted the assault on Sicily. After Sicily, the regiment participated in the Italian Campaign, including the landings at Salerno and Anzio, and the brutal mountain fighting on the way to Rome. Next, the Regiment landed in Southern France with the VII Army invasion forces. Late in December, 1944, the Regiment crossed the German border, but was ordered to hold up, and then to withdraw as VII Army spread out and shifted forces north in reaction to the German Ardennes Offensive, better known as the Battle of the Bulge. As the American units withdrew from exposed positions in Germany to a shorter, more defensible line along the border, the 157th Infantry Regiment found itself falling back to occupy fortifications in the French Maginot Line, vicinity Niederbronn. A German offensive against VII Army, intended to relieve the

American pressure on the Bulge, was launched on 1 January, 1945. This offensive,

known as Operation Northwind, drove deeply into the Lower Vosges Mountains, at the

juncture of the American XV and VI Corps. However, the weak American forces fought

stubbornly and after a few days the German salient was definitely contained. The

point of the German salient rested just north of the Once the German attack was halted American efforts were directed to reducing the salient north of Reipertswiller. The 157th Infantry Regiment, viewed as a relatively rested unit since the majority of the fighting had focused to the west of Niederbronn, was selected to push back the nose of the salient. 10 January: The regiment occupied its defensive sector with 1st and 3rd Battalions and 1st Battalion, 315th Infantry Regiment (attached) on line. Second Battalion was in reserve. Active patrolling and sporatic firefights characterized regimental operations. While the German attack had been stopped, bitter fighting still ensued along the whole periphery of the salient as the enemy vainly attempted to regain the initiative. Late in the afternoon 1st Battalion, 314th Infantry (attached to 45th Division) was thrown back from positions on Hill 388, just north of Reipertswiller. In response, 2nd Battalion, 157th Infantry (Companies E, F, G, H) was ordered after dark to move by truck to Reipertswiller, and attack immediately to retake Hill 388. Movement began after dark, and the battalion was not assembled in Reipertswiller for several hours. The night attack was launched just before midnight, and the men moved up the slippery, forested slopes of a hill they had never seen in daylight. 11 January: Second Battalion occupied the hilltop positions early in the morning without meeting any resistance. This situation changed dramatically with first light. For the rest of the day the Germans attacked the battalion, infiltrated the lines, and engaged the American troops with deadly accurate sniper fire. The fighting was close, bitter, and continuous, but the battalion managed to hang onto the objective. 12 January: Second Battalion continued defensive fighting near Hill 388 throughout the day. Late in the night the battalion was alerted to prepare to turn over positions to the 314th Infantry, which had reorganized, and then to assemble in Reipertswiller. 13 January: Relief of 2nd Battalion began just after midnight and the companies were assembled in Reipertswiller at dawn. The battalion was ordered to move immediately to occupy defensive positions vicinity Hill 415, northeast of Reipertswiller. Lieutenant Colonel Brown, the Battalion Commander, was told the rest of the Regiment would arrive later in the day and would attack the next morning -- 2nd Battalion would be in reserve during the attack. G Company moved to the top of Hill 415, proper; F Company took positions to the left (west) of G Company; and E Company occupied a reserve position generally behind F Company. There was heavy shelling all day as the battalion relieved elements of the 276th Infantry (attached to 45th Division). First Battalion, 157th Infantry, moved late in the afternoon to occupy positions to the right (east) of 2nd Battalion. A Company moved to a position to the right front of G Company, on the forward slope of Hill 415. B Company went into position to the right rear of A Company, on the edge of a draw -- no American unit could be found to the right of B Company; the area was open all the way to Rehbach. C Company occupied a reserve position to the rear of Hill 403. Third Battalion moved into an assembly area about 3 kilometers behind the line. During the night, small groups of the 276th Infantry were located in the woods, where they had been abandoned during the frenetic withdrawal of their unit. 14 January: Just after sun-up ist and 3rd Battalions kicked off the attack. C Company leading the 1st Battalion attack, intended to attack from the east side of Hill 415 and follow across the east side of Hill 363 to its objective, the Hill 390 ridge. However, navigation in the snowy forest was very difficult; the company missed a trail fork, moved behind Hill 415, and passed through F Company, on the west side of Hill 415. The company commander realized his error, but there was nothing to do except notify battalion and keep going. Just past the front line, C Company hit stiff resistance and was driven to ground just short of RJ 328. The whole column was halted and subjected to heavy artillery fire. Third Battalion, moving in column, passed through F Company and ran into the rear of C Company. C, I, K, L, and F Companies, clustered together in a small area, were subjected to heavy shelling. After awhile, 3rd Battalion moved off to the left (west) and as they got out of the shelling, the companies peeled off the march column to resume a northerly route toward Hills 400 and 420. The battalion halted for the night about halfway to those hills: I Company halted for the night in the Fliess Draw, just to the west of Hill 363; L Company halted on the forward slope of Hill 341; and K Company halted in the Spielbuchel Draw along the trail between Hills 341 and 401. Unbeknownst to Lieutenant Colonel Sparks, 3rd Battalion Commander, the 1st Battalion, 315th Infantry, had moved into the area immediately north of Reipertswiller early that morning and had also attacked to the north. C Company/315th took Hill 401 by the end of the day. B Company/3l5th and K and L Companies/l57th had cris-crossed each other's trails during the day; at dark, B/315th had established itself between K and L Companies. Second Battalion remained in place during the day, under heavy shelling. 15 January: First Battalion/3l5th remained in place during the day, and was alerted to withdraw the next morning. Third Battalion moved out again at daylight and brushed through relatively light resistance from remnants of the 476 Grenadier Regiment, 256 Volksgrenadier Division. L Company was the first of the 3rd Battalion units to move onto the hill mass. Just before noon the company came through the saddle between Hills 420 and 400 and moved east onto Hill 400, taking several prisoners and establishing a line running along the northern slope of the crest and hooking back to the south at the right flank. There was no contact with anyone to the right or to the rear, or with I Company which occupied the saddle later in the afternoon. Just after L Company got onto Hill 400, K Company climbed onto Hill 420, having come through the saddle between Hills 400 and 420, and occupied the hill with the main line of the company facing generally to the west . However, 1st Battalion, attacking on the right, was held up by determined resistance centering around RJ 328 and was unable to progress beyond this point. C Company could make no headway against Hill 363. B Company conducted an attack across the Brambach Valley to seize the ridge extending northeast from Hill 415, but was repulsed after gaining the ridge. At about 1600 hours, I Company also moved through the saddle. Two platoons occupied positions on the northern side and the remaining platoon defended the south side of the saddle. I and K Companies were physically tied together, but neither had contact with L Company. Occupation of the hills by 3d Battalion constituted a penetration of the German Main Defense Line, and in response, the German Corps Commander ordered the uncommitted 1lth Regiment (Reinhard Heydrich), 6th SS Mountain Division (Nord) to retake the critical terrain. Almost as soon as I Company arrived on the saddle, the hills were subjected to two or three violent German counterattacks -- some Germans managed to get behind the battalion. SS troops participated in some, if not all, of these attacks. By the end of the day, I Company -- which had arrived on the hill with 100 men -- was down to 91 GIs. L Company was down to 95 of the 106 men who had gained the hill, and K Company had 79 men left out of the 99 who had moved onto the hill. In response to the attacks against 3rd Battalion, E Company was ordered to move from its reserve position to Hill 341 to block against any German breakthrough of 3rd Battalion's positions. This move was accomplished without problem and E Company dug in on the northern nose of the hill, where L Company had spent the night of 14-15 January. 16 January: C Company was ordered to bypass the German resistance on Hill 363, and to join 3rd Battalion; this the company managed to do and by about noon it had moved to Hill 420 and occupied positions to the rear of L Company. The company was to have continued the attack by moving down the ridge line to the east, but this attack never materialized. German infiltrators were slipping around the flanks of the hills, and when the C Company supply sergeant attempted to bring three jeeps of supplies to the company later that afternoon the convoy was ambushed and all but two of the men were killed or captured, and the jeeps and their supplies were lost to the Germans. After C Company linked with L Company on Hill 420, B Company was ordered to move along the same route, again bypassing the German defenses on Hill 363. As B Company moved down the slope of Hill 415, mortar fire wounded several men, including Captain Stough, the Commander. The only other officer in the company, Lieutenant Castro, assumed command and continued the movement. However, the company was stopped at the base of Hill 341 by intense German fire from new positions behind L and C Companies, and was driven to ground. Since B Company's effort to link with 3rd Battalion on the

right flank had been stymied, Regiment decided to try to link with the forward troops

by attacking toward the left rear of K Company. G and E Companies were ordered to

move to Hill 401, relieve elements of the 315th Infantry (attached to 45th Division)

and to attack down the ridgeline to link with K Company on Hill 400. Both companies

conducted the move to Hill 401, and late in the afternoon began to move down the

ridgeline in column, with G Company in the lead. Germans cut the column after dark,

separating G Company, one platoon (2nd) of E Company and some H Company machine gunners

from the rest of the column. Efforts were made to fight through this German

resistance, but to no avail. Those elements north of the break in the column

joined with K Company well after dark and occupied positions facing the ridgeline

along which they During the day Regiment created a Composite Company from members of the Regimental Headquarters Company and the Regimental Antitank Company. This company was ordered to block the Spielbuchel Draw between Hills 335 and 350; it moved into position late in the afternoon. Resupply efforts through the valley were successful during the day and night, and these operations funnelled through a trail leading up the rear of the saddle. Two light tanks and two M-8 Scout Cars managed to reach the forward area, although they did not have sufficient traction on the steep, slippery trail to get over the saddle. The Tanks were ordered to remain to bolster the rear defenses of I Company, but the Scout Cars were to return. The two light tanks took positions in the I Company line, facing to the rear in the saddle between Hills 400 and 420. Although some of the wounded were evacuated, there were 16 litter cases who could not be carried on the scout cars. By midnight, 16 January, the Germans had succeeded in surrounding the hills, which were well forward of the general US line. From this point on, there would be no reinforcement or withdrawal of the surrounded 3d Battalion and the other men who had managed to break through to the hills. Although the two other battalions of the 157th Regiment, two additional battalions attached to the regiment in the next few days, a regimental composite company, and a platoon of medium tanks continually attacked to break in to the surrounded troops, no future efforts would succeed in breaking the German ring. When the Germans closed the ring around the men on these hills during the night of 16-17 January 465 American soldiers found themselves surrounded. 17 January: Third Battalion and attached units defending Hills 400, 420, and the saddle between them continued to fight off German attacks and to suffer heavy shelling. That portion of E Company not cut off on the hills tried to attack down the ridgeline, but was not successful. During the night the Composite Company was ordered to link up with B Company on Hill 341. The company set out in two groups: one group, accompanied by two tanks moved up the Spielbuchel Draw; the other group, with the company commander, headed cross-country. Both groups encountered heavy resistance and were driven back. The company commander was killed. Late at night, Lieutenant Talkington, 3rd Battalion Ammunition & Pioneer Platoon Leader, guided a light tank with a trailer of supplies to the forward area. These were the last supplies received by the surrounded men. 18 January: Shortly after midnight, LT Talkington tried to return to the rear with the light tank and trailer. Not far from the hills, the tank was ambushed at close range. Talkington, lightly wounded, escaped in the forest and regained the lines. The three tank crewmen were all wounded and captured. German infiltrators, in strength, had finally closed all supply avenues through the valley -- the hills were well and truly cut off. Just at dawn the Germans launched a violent counterattack against the G and E Company positions. The attack was so sudden and was initiated at such close range that there was hardly time to react. Some survivors reported that the Germans used flame throwers in this attack. The E and G Company men were thrown from their positions. Many men were killed or captured and all machine guns (possibly as many as four) were lost as the survivors dashed back into the K Company line. Only 18 men from G Company made it to the K Company line, and it is possible that all the E Company men were lost, for there is no further mention of this platoon in the journals and reports. Desperate to break in to the surrounded troops, Regiment

ordered all battalions to renew their attacks with all available men. None of these

attacks succeeded. Third Battalion's Antitank Platoon attacked across Hill 350, but

almost immediately ran into Germans, were driven to ground and pinned down. A squad

leader escaped at great risk, made his way to the battalion forward command post, and

informed Lt. Col. Sparks of the platoon's plight. G Company, 179th Infantry, was attached to the Regiment and went into position in the Fliess Draw, facing Hill 363. The remainder of the battalion was alerted for attachment to the 157th the following day. Upon moving into the area in the morning G Company, 179th Infantry, and a section of medium tanks moved up the trail and attacked Hill 363 from starting positions just to the east of Hill 341. The tanks remained on the road and fired over the heads of the attacking troops. The attack failed. G Company, 179th Infantry, assumed defensive positions and fought off German patrols attempting to infiltrate into the draw around both its flanks. In the evening the tanks withdrew. In the evening the remainder of the Composite Company was once again ordered to link up with B Company on Hill 341. This mission was accomplished, and the 20 or so remaining Composite Company men joined the equal number of B Company men who remained on the hill. 19 January: While the soldiers trapped on the hills continued to resist German attacks and heavy shelling, Companies E, and F, 179th Infantry, arrived during the day and were ordered to attack up the Spielbuchel Draw to break in to the surrounded companies. The two companies were able to progress to a position on line with B Company/Composite Company on Hill 341 before they were stopped by German fire. Subsequent attacks, even with direct tank support, were repulsed by the Germans. A and F Companies and G/179th renewed attacks against Hill 363, again without success. G Company, 179th Infantry, and a section of medium tanks attempted to reach C Company and Hill 400 by attacking directly up the trail from a starting point near Hill 341. The attack failed, and the troops and tanks withdrew. The remnants of E Company, bolstered by cooks and headquarters personnel, renewed attacks down the ridge leading to Hill 400, also without success. Late in the day, 2nd Battalion, 411th Infantry, was attached to the 157th. The battalion established an assembly area and prepared to attack the next morning to take Hill 363. 20 January: Early in the morning 2/411th attacked over Hill 415, heading for Hill 363. It conducted three unsuccessful, costly attacks. In the afternoon an attempt was made at aerial resupply of the surrounded troops. No supplies got the the men due to weather. The men could hear the planes, but all supplies fell into German hands. Also in the afternoon the Germans sent a party under a white flag to give a message to the American commander of the surrounded troops: Further resistance is futile; surrender by five o'clock or suffer the consequences. When Regiment was notified of the ultimatum, the surrounded troops were ordered to break out by attacking down the ridge toward Hill 401. The leaders rushed to inform the men that at the precise

time the German ultimatum ran out, the men would try to attack to the rear. An

artillery preparation was laid on to blast clear a path along the ridge and then to

follow the men off the hill. Non-ambulatory wounded were told they would have to

remain in their holes and place their fate in the It took a long time to pass the word about the attack and there was a delay in assembling the men. it was snowing heavily, and just as most of the men were out of their holes and trying to get formed up, the American artillery barrage came in -- right on top of the GIs. Many were killed and wounded. There was much confusion and, although some groups tried to proceed with the attack, there was little cohesion and the German troops swarmed upon the shocked men. The last words Regiment heard from the group came over the K Company radio: "Stop the artillery. We're surrendering." Late that night the US corps withdrew, leaving the survivors to their fate. Only three soldiers (two from I Company and one from K Company) returned to the US lines. Four hundred and six American soldiers were captured -- according to German records, most of them were wounded, Fifty-six American soldiers lay dead or dying on the hills. In the fighting to gain the hills, and then to break in to the surrounded troops another 88 American soldiers were killed and more than 350 were wounded and evacuated, and another 300 were evacuated for illness or injury. In the five-day fight for these hills, losses to the US forces totalled over one thousand men. To this day twenty of the 144 soldiers killed in this fight remain listed MISSING IN ACTION.

This article written by Dan Dougherty who is publisher of the quarterly newsletter, Second Platoon, Co. "C", 157th Regiment, 45th Infantry Division. GETTING RELIGION When the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) folded in March of 1944, my unit at St. Louis University was sent (kicking and screaming all the way) to the 44th Division on maneuvers along the Sabine River that joins Louisiana and Texas. All of the ASTP guys were privates and had no infantry equipment and most had no infantry training but the maneuvers did not halt one second while hundreds of us were integrated into rifle and weapons companies. I’d had a seventeen week infantry basic training prior to ASTP but for the guys who had given up cushy jobs and rank so they could go to college in the Army, a really bad dream had come true. After a week or so of slogging around in the muck, the

maneuvers recessed on Thursday of Easter week for a two day break. The next day -

Good Friday - the division was marched to a large hillside where we sat on our

helmets. After the inevitable Army wait, a jeep drove up at the bottom of the hill

and an altar was set up complete with loud speakers. Then a Catholic mass was said

for the entire division. Some of us closed our eyes and plugged our ears in

silent protest. The next day the maneuvers resumed. The Army in its infinite wisdom

had decided that since no one would be able to celebrate Easter that year, the entire

division - Catholic, Protestant, Jew and agnostic alike - would observe Good Friday

together. I’m sure many families and Congressmen heard that week about the U.S.

Army’s version of the separation of Some months later, Leonard S. "Pinky" Popuch (ASTP at the University of Minnesota) and I were a rifleman and BAR gunner respectively in K Co of the 324th Infantry Regiment fighting in Alsace with the Seventh Army. The 44th had started fighting in October when it relieved the 79th Division and in the big push which began November 13 we helped take Strasbourg ten days later and our regiment was the first U.S. Army unit to reach the Rhine. Then one morning - now late January 1945 - Pinky and I were abruptly promoted from Pfc to S/Sgt and sent to the 45th Division. It was the only time in my military career that a jeep was waiting for me and we weren’t even given time to say goodbye to guys we’d been with for almost a year. That afternoon we found ourselves squad leaders in different platoons of C Co of the 157th and learned we were one of six companies being reformed after the wipeout at Reipertswiller (1). Hundreds of replacements arrived from the depots and non-coms came from all Seventh Army divisions including Ben Ewig from the 103rd. Officers were scrounged from everywhere including Ft. Benning. We trained for one week and went back to the line. Instant infantry. Now, there must be an Army manual somewhere that says that one week after joining a new unit, the G.I.’s are to have a mandatory session with the Chaplain because, sure enough, after supper on the final day before we were to leave for the front, we were herded into a French school house to have a session with Father Barry, the First Battalion Chaplain. I prepared once again to close my eyes and plug my ears but this time it was different. The room was dimly lit and I could hardly see but the voice was loud and clear. The Chaplain’s message was brief, fifteen minutes at most. There was no religious service and no prayer. Instead, in some very direct language Father Barry told us why we shouldn’t desert! The G.I’s of C Company had gotten religion - Thunderbird style! The following biography of Father Barry is from Dachau - The Hour of the Avenger (2) by Howard A. Buechner: Capt. Joseph D. Barry - Chaplain. Father Barry of Syracuse, New York was awarded the Silver and Bronze Star Medals for assisting in the evacuation and comfort of wounded and dying soldiers on Anzio, under extremely Hazardous conditions. He was born in 1903 and died in 1985. For many years he was associated with Notre Dame University and was Chaplain of the Notre Dame football team during the coaching era of Frank Leahy. Father Barry joined the 157th Infantry Regiment at Camp Barkeley, Texas, in 1943, and "went all the way" to war’s end in Munich, Germany. He was a man of unfailing good humor and outstanding courage and was one of the most beloved clergyman of the 45th Division. It is easy for me to picture Father Barry in the locker room at halftime with the Irish down by ten points. He’d be light on theology and heavy on "Don’t quit fighting!" (1) See Monograph #9 on Operations near Reipertswiller by Felix Sparks available from 45th Division Assn, 2145 N.E. 36th St. Oklahoma City OK 73111, $2 plus $3.25 S&H per order. (2) Available from Thunderbird Press, 300 Cuddihy Drive, Metairie, LA 70005. $14.95.

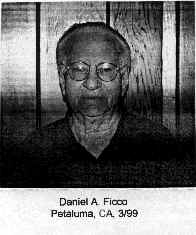

The following article appeared in the Second Platoon, which is a quarterly newsletter written and published by Dan P. Dougherty. Dan served as a Squad Leader and then Platoon Guide in the Second Platoon of "C" Company, 157th Regiment, 45th Infantry Division. SNEAKING INTO A PRISON CAMP by Daniel A. Ficco

Editor’s note: Dan Ficco went overseas with C Co and participated in amphibious landings at Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, and Southern France. He was subsequently captured in Reipertswiller in Alsace on January 17, 1945. Despite the fact he has a serious health problem, Dan has at my request made the time and effort to write up some of his experiences which I’m pleased to share with readers. You’ll see he too "served" in C Company in the post-Reipertswiller era! Dan is now eighty years of age and resides in Petaluma, California. I was Ed Speairs’ 1st Sergeant, Company Clerk, Supply Sergeant and anything else we needed. He was a very good company commander and he and Felix Sparks were two of the best officers I have known. I can tell you my experience of escaping the prison camp at Mooseberg, Germany near Nuremburg. It is about 30 kilometers north of Munich. In a POW camp there were always rumors about what was happening. They said 1st Battalion, 157 Infantry was in Munich. I crawled through a hole I made in a fence just before dark and got into Mooseberg. A friend of D Co came with me. We crossed a street and saw a box of cigars in a store window. There were many German soldiers in town and to cause a diversion I threw a rock through a window while my friend grabbed the cigars. The German soldiers came running to the store and we ran down a ditch. It took us a few days to get through the German lines and across the American lines. When I found C Company, I didn’t know many men - just the cooks and a few others who had been there before. All my personal belongings were gone - pictures, a camera and several pistols I had picked up. The first thing I wanted was food. I ate too much and was sick for a couple of days because my stomach couldn’t handle the solid food. My normal weight was 175 pounds and I now weighed on 90. I never thought I would sneak into a prison camp. Father Barry was our 1st Battalion chaplain and another of the best. We’d had a lot of experiences together. He came to C Company and told me to go back in the prison camp! It had been liberated and we would be flown to a RAMP Camp (Reclaimed American Military Personnel). Father Barry couldn’t take us back in the camp so he took us near there and we crawled back in through the same hole!

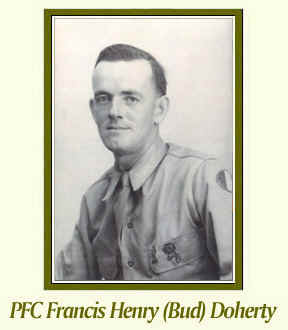

A TRIBUTE TO PFC FRANCIS HENRY (BUD) DOHERTY

Company L, 157th Infantry Regiment, 45th

Infantry Division, 7th Army FRANCIS HENRY DOHERTY was born on June 22,

1915, in Malone, Franklin County, New York. He was the eighth of nine children of John

Henry Doherty and Caroline McCaffrey Doherty, and the great grandson of early nineteenth

century northern New York settlers and Irish immigrants Hugh Doherty and Bridget Meighan

Doherty. -- Edward J. Doherty --

THE STORY OF ASCHAFFENBERG My good friend Bob LeMense was going through some of his World War II memorabilia and found a pamphlet entitled, "The Story of Aschaffenberg". This pamphlet is a condensation of the newspapers and radio coverage of the siege of Aschaffenberg. It was prepared by the Public Relations Office, 45th Division, for the troops of the 157th Infantry Regiment who reduced the city to rubble and forced its capitulation after six days of bitter assault. In it are copies of press releases that were filed with the major newspapers and syndicates of the United States. From the pamphlet, I selected the article that appears on the next few pages. I might add, that Bob LeMense was a platoon leader, 3rd platoon, in company L, 157th Regiment. It was Co. "L" that took the town of Dachau which adjoins Camp Dachau. Bob was one of the editors who helped to put the 157th Regimental Book together. Many thanks for your support and encouragement. Talk about history repeating itself. Aschaffenberg was taken by the 45th Division, April, 1945. Exactly 54 years later, even to the months, we have a similar situation in Kosovo. As I was reading and typing the Aschaffenberg story, I was amazed at their similarity. The following pictures show the barracks that housed Major Lambert’s future German officers and convalescents. It was on a grassy incline, as shown in a few pictures, that many of our bazooka men were picked off by snipers from behind. After the war, American troops occupied the barracks for a number of years.

The Story of Aschaffenberg WITH THE 45Th DIVISION IN ASCHAFFENBERG (April 4,1945)-- This is the story of the amazing climax of the siege of ASCHAFFENBERG. Here is what happened behind the shattered and scarred walls of the city, known to grim-humored infantrymen of the 45th Division as !Cassino-on-the-Main!. This is not the story of the endless bombing and shelling of a fortress town. It is the record of one man's fanaticism and of his ultimate capitulation. Used as a replacement and convalescent center by the Wehrmacht, ASCHAFFENBERG was a quiet town whose peaceful serenity was broken only occasionally by the screams of some poor tortured soul in the Gestapo headquarters. German troops, returned from hospitals awaiting shipment to their parent units, strolled through the town and admired the Bavarian countryside. At night, the steady drone of American planes reminded the townspeople that there was a war being fought somewhere far to the west on the other side of the glorious defenses of the Siegfried Line and the Rhine River. On March 15th, the 4th Division penetrated the Siegfried Line. Three days later veteran Thunderbird troops were through the line. March 26th the division crossed the Rhine River and sped across the fertile valley of the Rhine. The war came to ASCHAFFENBERG on the 27th of March. There were two men in the town who were responsible for the execution of der Fuehrer's orders to defend the Reich. One was a short, bespectacled HEIMUTH WOHLGEMUTH, Kreisleiter (Nazi Party Leader for the County); the other was close-cropped, Prussian- backed Major of the Wehrmacht, Lambert, military commander of the garrison. Rumors of the Americans' advance preceded the troops with alarming frequency. Major Lambert and the Kreisleiter conferred. When the 45th Division's tanks rolled across thirty miles of the Rhine valley and headed for ASCHAFFENBERG, the two leaders of the town knew that their hour had come. Here was the chance to show their love for the Fatherland. Here was the chance to place themselves at the right hand of the Fuehrer. There were more than three thousand troops and many officers with rank as high as colonel among the casual convalescents in the replacement battalions of ASCHAFEENBERG. Major Lambert ordered all troops to report immediately for active duty, all officers to assume active duty of the troops. !These orders will be carried out immediately,! He proclaimed. Then the Kreisleiter issued an order to the civilians. He designated Wednesday and Thursday (March 28, 29) as days on which the civilians who wished to evacuate the town could leave. All others he said, would be used in the armed defense of the town. The ASCHAFFENBERG training area was dotted with concrete and steel pillboxes that had been used for training purposes. These casements were linked by a trench system and the hills around the town made an excellent defense. Lambert manned the physical defenses and sat back to wait. But one officer had not reported for duty. Word came to the Castle which was being used as a joint Gestapo and military headquarters that LT. FRIEDL HEILMANN was still in town and had not assumed his new command. Lambert, fired by the frenzy of his fanaticism, ordered Heilmann broought before him. There was no trial, no court martial. Wednesday morning, Heilmann was hanged from a buttress of the castle. His body swung in full sight as a visible reminder of what would happen to deserters, until an American artillery shell cut it down. The siege had begun. All day long, planes swooped over the town as heavy demolition and fragmentation bombs mush-roomed below. Great artillery pieces pounded the town. Rubble and debris showered into the air. Houses crumbled and the factory’s steel beams were twisted with the concussion. For four days the town was contorted in a convulsion of explosions. Some of the troops, unable to take the continued pressure, attempted to slip through the lines of our forces. On command of Lambert, they were machine-gunned and killed. Civilians who had managed to save themselves by hiding in the cellars of the city tried to get out. Again, Major Lambert ordered his machine guns to fire on them. They were killed. In the garrison, officers who ranked the major attempted to persuade him to surrender the garrison. One colonel who later was captured by the Thunderbird troops, said that he had pleaded with the major to surrender the garrison, but the major had told him to go back to his post or be shot. Yesterday, fifth day of siege, prisoners reported that Lambert had brought in 50 SS troops. These troops were ordered to shoot and kill anyone who did not resist to the end. Again, Lambert issued an order. The garrison of ASCHAFFENBERG would fight to the last man. Still the bombing and shelling continued. One lieutenant,

taken prisoner, estimated that more than 1500 dead lay in the town. But the

resistance in the town, fired by the threat of death at the hands of the SS went on.

Thunderbird troops, forced a wedge into the southern tip of the town. From room to

room they fought into the town. It wasn’t a case of cleaning one room and having

the rest of the house surrender. Each room had to be cleared in a separate As the 45th Division troops inched ahead, German snipers infiltrated through the heaps of debris and harassed the doughboys from every possible vantage point. In some cases, civilians sniped at our troops. A Luftwaffe captain, almost isolated in a house, attempted to surrender his little group. SS men fought through to him, hauled him back to Lambert and again, without trial, on arbitrary order from the commandant, he was shot. Late yesterday morning, Lambert called in his senior officers. "I am going to see if we can reinforce the garrison," he said, "I will be gone tonight, but I will be back. I order you to remain here and fight to the last man. When I come back, you’d better be here. The garrison, under threat of ultimatum, continued its resistance. On the night of April 2nd, COL WALTER P.O’BRIEN, commander of the 157th Infantry that had besieged the town, reshuffled his battalions. He sent LT COL. RALPH M. KRIEGER (Craig , Colorado) to take his battalion, the First, into the northeast end of town. In the south and southwest, O’BRIEN sent the third battalion under LT. COL. FELIX L. SPARKS of Miami, Arizona. And the regimental commander completed his ring of steel around the fortress city with his second battalion, commanded by MAJ. GUS H. HEIIMAN (University of Virginia). The squeeze was on. Throughout the night of the 2nd and the morning of April 3rd, the squeeze tightened as the 45th Division troops converged on the town. All avenues of escape were cut. All hope of reinforcing or supplying the garrison were ended. By nine o’clock of the night of the second, eleven hundred prisoners had been taken out of the town. But those who remained fought bitterly or died in place. In the meantime, during the previous three days of the siege, Lambert ordered the execution of four more men who attempted to leave the city. On one grisly product of his fanaticism, Lambert hung a sign "I tried to run away." The ghastly warning swung from a telephone pole until after the surrender of the town.. Lambert never left the fortress. Hemmed in on all sides and with the iron jaw of the 157th’s vice closing in on him, he found it impossible to leave the city. As the total of dead mounted in the fortress and bombardment increased in its intensity throughout the night of the 2nd, Lambert began to think of capitulation. At 0700 this morning, he ordered an American soldier who had been captured last Sunday, to be brought before him. Then he designated a captain of his staff to go with the G.I. to negotiate for a surrender. He gave the captain a note to the American commander. At COL. O’BRIEN’S C.P.. the captain delivered his message. COL. O’BRIEN was in no mood for bargaining. "Tell Lambert, he said, "That he doesn’t wave white flags from the castle as a sign of unconditional surrender, I’ll level the place to the ground!" A few moments after the captain returned to the garrison the white flags from the castle fluttered out of the highest windows. The siege of ASCHAFFENBERG has ended. At 0900, Major Lambert, dressed in high polished boots and a long green overcoat with a peaked cap of the Officers Corps of the Wehrmacht, strode out of the besieged town accompanied by his staff. Formal surrender was made to COL. O’BRIEN, but the 45th Division commander was not content merely to accept the capitulation. He ordered Lambert to return to the garrison, with an escort of men from G Company. Riding in the first jeep of the convoy, Lambert called out to the remaining men of the garrison to lay down their arms and give up. The long procession that leads to the PW cage was on its way. Awaiting evacuation, Lambert looked once at the still-smoldering ruins of the town which his fanatic threats had brought to shambles. Then Major Lambert, former commandant of the garrison, turned his back on ASCHAFFENBERG. SECRETARY STIMSON SPEAKS WASHINGTON, April 7 (ans)—The German people were warned by Secretary of War Henry L. Simpson yesterday that they have only a choice between immediate unconditional surrender or the same form of capitulation "a little later after much more of the Reich has been destroyed city by city."

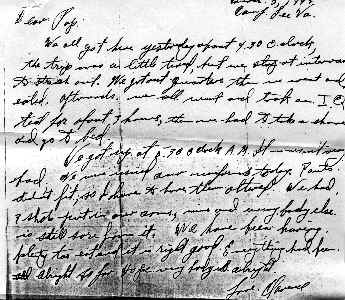

World War II Experiences of Clarence B. Schmitt This is a story told by Clarence B. Schmitt who was a member of Co. "M", 157th Regiment, 45th Infantry Division When the war started, there were five in my family drafted but the sixth brother John, they would not take as he was older and was involved in war work. When we wrote to our father, my brother John would save all the letters. I was drafted and sent to Camp Lee, Virginia. After a short stay at Camp Lee, I was transferred to Camp Wolters, Texas for basic training. Attached is a copy of the first letter I sent home dated 3/5/43. Also, a copy of the first letter from Camp Wolters dated 3/21/43. After thirteen weeks of basic training at Camp Wolters, we shipped out to the Port of Embarkation located in Shenango, PA. See letter dated 7/11/43. We were then sent to Camp Shanks, NY to board ships headed for Oran, North Africa. After a few in Oran, we were put on a train and went across North Africa to Bizerte. A couple of days later, we boarded an LCI and headed for the beaches of Salerno. I was assigned to Co. "M", 157th Regiment, 45th Infantry Division. We left the beach of Salerno and moved up a hill overlooking the Volturno River. The Germans knew we were there and they shelled us all day long with their 88’s. The next day they moved out and we crossed the Volturno River and setup in a grape orchard. It was harvest time and the Italians had picked their grapes. We watched them dump the grapes into a high vat and the girls took off their shoes, got up into the vat and stomped down on the grapes. That night we slept in the orchard and ate grapes. I fought all the way up the mountains above Venafro and stayed there for two months. Venafro is about twenty miles below Cassino. Christmas 1943, we were sent to the rear for a rest and I stopped at the Regimental medical tent. Before I knew it, I was sent to Naples. After a few days, I was transferred to Oran to the 45th General Hospital and remained there for a few weeks. It was determined that I be placed on temporary limited service due to bad feet. I then attended radio school from 4/10/44 to 5/.20/44. Received a certificate of completion. Latter part of June, 1944, reclassified and returned to Co, "M", 157th. On 8/15/44, made the invasion of southern France. October, 1944, I was admitted to the hospital for the second time near Grenoble, France.After a few weeks of hospitalization, I was reclassified and assigned to the 788 Engineer Petroleum Distribution Company located in Boone, Belgium. Our job was to lay gas pipe lines and build pumping stations to Wesel, Germany. I remained with the engineers until discharge. Webmaster’s comments: Clarence Schmitt wrote frequently to his father and every letter and V mail was saved by his family. His letters date from 3/3/43 to 12/3/45.

Clarence B. Schmitt Bernie Kaezorowski This picture was taken 9/28/98 at the 45th Infantry Division Reunion. Clarence was with Company "M" and Bernie Company "A"

These pictures, taken in Naples, Italy,1943. In the left picture, Clarence B. Schmitt is in the center, in the right picture Clarence is on the left.